SUPERVISION

{PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE}

MAKING THE MOST OF SUPERVISION

This article is reprinted with permission from the Australian Counselling Research Journal www.acrjournal.com.au

By Dr Judith R Boyland

Supervision is a process familiar to all practitioners who work in the field of allied health, and to a wide range of professionals who work across diverse fields of human service. So, where did it all begin? According to Watkins (2013), Freud is typically credited with having initiated the possibility of supervisory practice by way of three events. These are recorded as being:

1. consultations with Breuer practitioners about their patients’ hysterical symptomatology during the 1890s;

2. the holding of weekly theoretical and case discussion meetings in his home beginning in 1902 (Davies, 2020); and

3. the tutoring, or ‘supervising’, of the father of a little boy about how best to work with his son (referred to as ‘Little Hans’) who was experiencing a host of psychological problems.

Freud’s discussion meetings have come to be thought of as the informal beginnings of supervision, whereas his work with Little Hans’ father has been considered the more formal beginning of supervision. Although Freud never articulated an actual theory of supervision, he still tends to be thought of as our ‘first supervisor’ – a somewhat contentious issue with those who would give this title to Josef Breuer, who was a mentor to the young Sigmund Freud and who helped him to set up his medical practice (Davies, 2020).

Breuer is perhaps best known for his work with a patient, pseudonym ‘Anna’, who was suffering from paralysis of her limbs, reduction in conscious awareness due to a state of anaesthesia brought on by pain-reducing medication, and disturbances of vision and speech. Breuer observed that her symptoms reduced or disappeared after she described them to him, and it is said that Anna humorously called this procedure ‘chimney sweeping’ and coined the term of ‘the talking cure’ for this process of talking about what was happening for her. Laying the groundwork for psychoanalysis, Breuer later referred to this therapeutic practice as the “cathartic method” (Gay, 1988, p. 65).

Moving into the 20th century, the Berlin Poliklinik, which opened on 16 February 1920, was the first clinic in the world to offer free psychoanalysis. It came to be the model for future institutes. It was the first establishment to use psychoanalysis as a treatment and to establish a tripartite training model of psychoanalytic education to prepare and supervise future psychoanalytic practitioners.

The man said to be ‘its heart and soul’ was Max Eitingon. Under Eitingon’s guidance, that preparation of practitioners involved three crucial components:

■ seminars – didactics focused on grounding in theory and conceptualisation of that theory into practice;

■ training analysis, where each student engaged in personal experience of psychoanalysis; and

■ supervised practical work. That model was to become known as the Berlin Model, or the Eitingon-Freud Model. The basic ideas that underlie the model – know your theory, know yourself, and know your practice through supervision – continue to be widely accepted as being of integral importance in any work that not only engages psychoanalytic processes, but also is related to any field of allied health work (Watkins, 2013).

Professional supervision – what is it?

Since its inception, supervision for the allied health professional has attracted a diverse range of definitions, highlighting the clinical, personal experience and teaching/learning aspects of the supervisory process. Stoltenberg and Delworth (1987, 34) focus on the clinical aspect when they define supervision as “an intensive, interpersonally focused, one-toone relationship in which one person is designated to facilitate the development of therapeutic competence in the other person”. For Lane and Herriot (1990, 10) it is “a therapeutic process focusing on the intrapersonal [sic] and interpersonal dynamics of the counsellor and their relationship with clients, colleagues, professional supervisors and significant others”. And for Marais-Styndom (1999), ‘support and learning’ is highlighted with reference to “a formal process of professional support and learning which enables individual practitioners to develop knowledge and competence, assume responsibility for their own practice, and enhance public protection and safety in complex situations.”

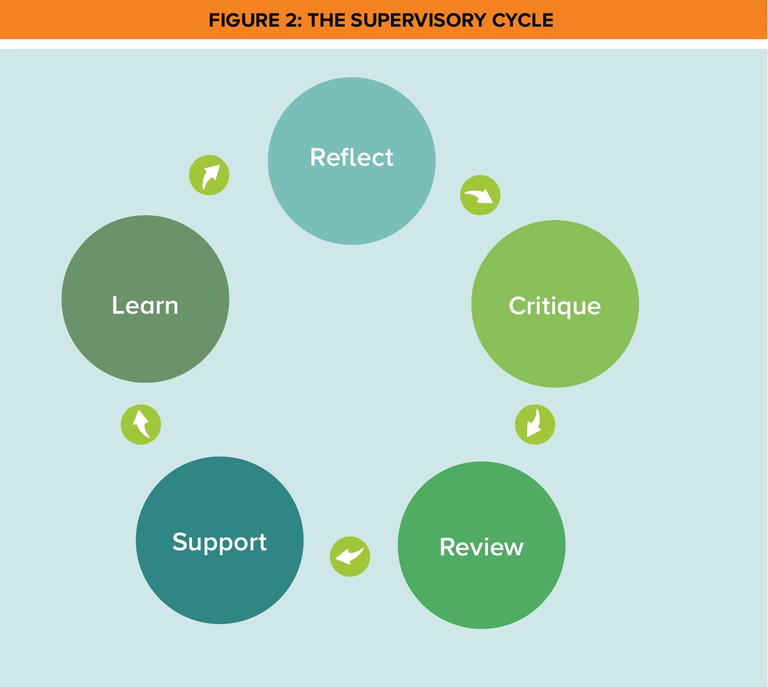

Falender and Hafranske (2010, 3) expand on the teaching/learning alliance where engagement is around “a distinct professional activity in which education and training aimed at developing science-informed practice are facilitated through a collaborative interpersonal process”. The notion of ‘reflective practice’ is introduced when Davys and Beddoe refer to a forum for reflection and learning by way of an interactive dialogue between at least two people, one of whom is a supervisor. This dialogue shapes a process of review, reflection, critique and replenishment for professional practitioners.

What is becoming evident is that supervision is a professional activity in which practitioners are engaged throughout the duration of their careers, regardless of experience or qualification. The participants are accountable to professional standards and defined competencies and to organisational policy and procedures.”

However, not until 2003 was the concept of business issues considered as an integral element for discussion in professional supervision. This development was introduced by Armstrong and subsequently tweaked to the current wording as featured in Armstrong (2018). Armstrong’s definition enunciates supervision as “the process whereby a professional can discuss personal issues (where appropriate and impacting on work); professional/ clinical issues; business issues; and industry/work-related issues with a qualified professional supervisor, who is usually more experienced than the supervisee, in order to identify and resolve professional concerns and emotional issues, and help the supervisee to evolve professionally in a positive manner.” (Armstrong, 2018).

Key functions of professional super vision

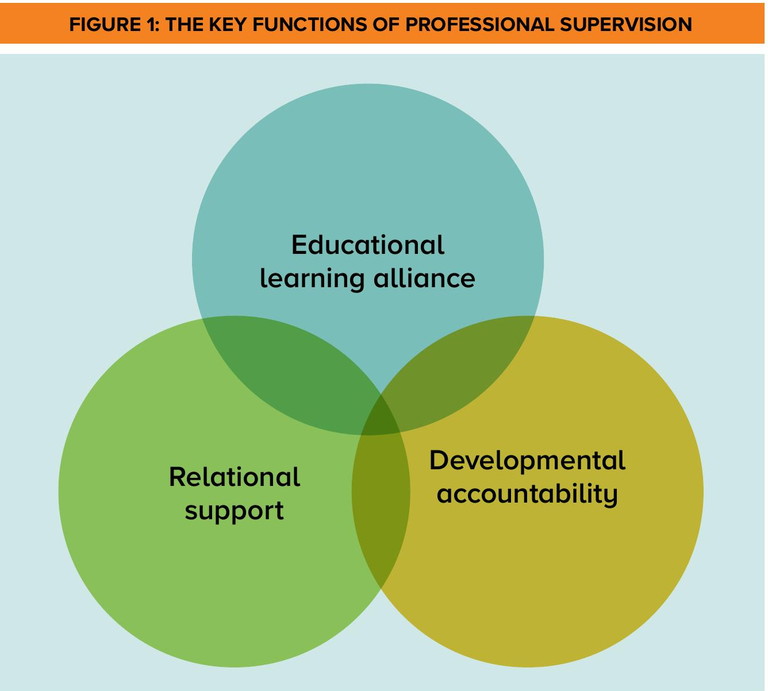

Reflecting on the collective nature of the notions put forth in defining ‘supervision’, it could be perceived as a forum for reviewing practice alongside policies and procedures and the ethical and practice guidelines and standards of the industry. Attention is focused on accountability for client outcomes while assisting the counsellor to clarify role and responsibilities within and across practice context. Thus, it might be ascertained that the key functions of professional supervision are educational, relational and developmental (Figure 1). These are not discrete – they overlap, interplay and complement.

The aim of supervisory education is to inform a better understanding of the client, the self, and the therapeutic process. The focus of learning is the knowledge, theories, values and perspectives that can be applied to enhance the quality and outcomes of practice. While attention is on developing practicebased knowledge, understanding and skills that will improve the competence and the confidence of the counsellor, it is the learning alliance between supervisor and supervisee that is integral to any educational activity.

The quality of the supervisory relationship is an important ingredient in the success of supervision. There needs to be a degree of warmth, trust, authenticity and respect between supervisor and supervisee, and recognition of the personal impact counselling practice can have on the practitioner as well as exploring how one’s personal space and emotional state can impact best practice outcomes. Strategies to deal with self-care are identified along with encouragement and validation. Working through personal-professional presenting issues as may be relevant and appropriate is one aspect of self-care, as is supporting the supervisee in recognising when external professional assistance may be needed in processing personal issues.

Why supervision?

Practitioners engage in professional supervision because of the need to meet requirements for industryspecific registration, to meet requirements for membership with a professional association, or to comply with requirements within an organisational structure. For example, the code of ethics and practice for the Australian Counselling Association (ACA) references the need for supervision as defined in articles 4.12.(a)i and 4.12.(a)ii:

4.12 ‘Competence’

4.12.(a)i Counsellors must have achieved a level of competence before commencing counselling and must maintain continuing professional development as well as regular and ongoing supervision.

4.12.(a)ii Counsellors must actively monitor their own competence through counselling supervision and be willing to consider any views expressed by their clients and by other counsellors (Australian Counselling Association, 2022. p.14)

Also stated in Queensland’s Clinical Supervision Guidelines for Mental Health Services is the mandate that “ongoing supervision for all clinicians involved in the delivery of mental health services is critical to ensure quality assurance in mental health practice, regardless of experience and level of appointment” (Queensland Health, 2009. p6).

More significant than compliance with a ‘need’ imposed from sources outside of self is the ‘want’ that emanates from one’s internal professional motivation, resulting in participating in supervision not because I must, but because I want to.

In consultation with a supervisor, the supervisee creates opportunity to reflect on all elements of practice – to look back on therapeutic engagements with clients and critique what was done, what was said, somatic transferences and counter-transferences, and the counsellor/client therapeutic alliance. One reviews what worked and what did not, and discerns what might be done differently next time. One also explores the impact that work is having on wellbeing and the cyclical flow of wellbeing impacting work. This is the space where the practitioner seeks and accepts support and where there is engagement in mentoring and learning activities that will be beneficial for both personal and professional development.

The purpose, goals and objectives of supervision can be summarised in the following statements:

■ monitor and promote welfare of clients seen by supervisee;

■ where supervisee is also a supervisor, monitor and promote welfare of clients seen by supervisee’s supervisees;

■ monitor supervisee’s holistic wellbeing and self-care;

■ promote development of supervisee’s professional identity and competence;

■ fulfil requirement for supervisee’s professional accreditation; and

■ fulfil membership and registration requirement of recognised professional body.

Thus, it can be determined that the focus of professional supervision is the need to promote learning, continually foster the therapeutic alliance and continually develop professional practice in all areas.

Role of the supervisor

The supervisor’s primary role is to ensure the supervisee’s clients are receiving appropriate therapeutic counselling. When the supervision is ‘supervision of supervision’, the supervisor has a dual role – that is, to do all in their power to ensure that the supervisee’s clients are receiving best practice supervision. This is to enable the practitioners, in turn, to ensure their clinical clients are receiving appropriate counselling and therapeutic support and intervention.

The supervisor also has an ethical responsibility to ensure the supervisee is aware of the importance of their own physical, emotional and psychological health, and support the supervisee in sustaining a healthy, holistic state of wellbeing. An additional element of responsibility that accompanies the supervisory role is being alert for any symptoms of burnout, transference, countertransference, dependency, co-dependency or hidden agendas in the supervisee and/or in the supervisee’s practice.

The supervisor’s primary role is to ensure the supervisee’s clients are receiving appropriate therapeutic counselling... This is to enable the practitioners, in turn, to ensure their clinical clients are receiving appropriate counselling and therapeutic support and intervention.

Where signs or symptoms of these reactions are detected, they need to be discussed with the supervisee and – if it is felt that there is potential risk to either the supervisee or the supervisee’s clients – the supervisor’s role is to direct the supervisee to seek relevant support. Furthermore, depending on the severity of the condition, the supervisee needs to be directed to cease practice until presenting issues are resolved.

If the supervisor discerns the supervisee’s clients are at risk of harm – physically, emotionally or psychologically – the supervisor must report to the relevant professional association and, in extreme circumstances, directly to the Office of the Health Omudsman, the Health Care Complaints Commission.

Duties and responsibilities of the supervisor

Summarising recommendations suggested in Pelling et al (2009 and 2017), the following list of supervisory duties and responsibilities is offered for reflection:

■ challenge supervisee to validate approaches and techniques in professional practice;

■ intervene where client welfare is deemed to be at risk – that is, welfare of supervisee, welfare of supervisee’s clients and – where applicable – welfare of clients engaged with supervisee’s supervisees;

■ provide information relating to alternative approaches for the supervisee to consider;

■ monitor basic micro-skills and advanced skills, including transference and countertransferences and dependency and co-dependency issues;

■ encourage supervisee’s ongoing professional education;

■ ensure supervisee is aware of scope of practice and ethical guidelines and commits to maintaining professional standards across all areas of practice;

■ challenge and support supervisee in professional growth;

■ monitor supervisee’s holistic wellbeing;

■ provide consultation when necessary;

■ discuss administrative procedures; and

■ for supervisees who are in private practice, discuss business practice issues as may be relevant.

Reflecting on the ethos expressed by the Victorian Department of Health (2012), it is suggested that for the supervisory process to be successful, it is important that both supervisor and supervisee are involved in planning processes and the setting of the agenda items, and that each party has a clear understanding of how their own position and positions of other stakeholders across the industry contribute to the wholistic success of the supervisory alliance. It is also imperative that the supervisor and supervisee hold mutual respect for each other, that the contributions of each party are valued, and that there are regular opportunities to meet and to discuss practice behaviours and matters of concern, and to discern ways to address emerging issues, to improve effectiveness in the field of operation, and to enhance client wellbeing.

Role of the supervisee

Each participant in the supervisory relationship has a role to play. For the supervisee, that role is to engage in processes of reflective practice through exploration and critical reflection and, in that reflection, to be open to learning that is focused on knowledge, theories, values and perspectives that can be applied to enhance the quality and outcomes of practice. It is also the role of the supervisee to explore how personal reactions and emotional wellbeing are impacting on the counsellor/client relationship and all aspects of practice.

Pivotal to the role of the supervisee is the review of client outcomes, therapeutic and administrative practices, organisational policies and procedures, and ethical and practice standards of the industry. A significant aspect in the broader industry is for the supervisee to reflect on the wider professional context of the field of practice, to be aware of the organisational context of practice and to clarify one’s own role and responsibilities within the specific context of engagement.

Duties and responsibilities of super visee

For the supervisory process to be effective, both supervisor and supervise need to be engaged and committed. The supervisee’s engagement begins with establishing a daily routine of reflective practice, which begins with taking time to think about work and the practice of client support (Morrell, 2013). This involves focusing on the basic needs of safety, belonging and dignity, and discerning how autonomic regulating behaviours are working to enhance or relationship with both the self and the client.

In a similar vein as defining duties and responsibilities of the supervisory role, the following list of supervisee duties and responsibilities, sourced through personal discussion with clinicians and extracted for Pelling et al. (2009) and Pelling et al. (2017), is offered for reflection:

■ uphold ethical guidelines and professional standards;

■ discuss client cases with the aid of written case notes and video/audio devices as may be appropriate in relation to specific contexts;

■ validate diagnoses and professional judgements made;

■ validate approaches and techniques used to address presenting issues;

■ consult supervisor or designated contact person in cases of emergency;

■ maintain a commitment to professional growth, ongoing education and the profession;

■ complete homework tasks as may be either negotiated or directed;

■ implement supervisor directives in subsequent sessions; and

■ be open to change and incorporate alternative methods of practice.

Qualities and skills of an effective supervisor

Referencing the emergence of ‘counselling supervision’ as a professional specialty, Dye and Borders (1990) highlight the notion that professional supervisors require specific training in processes of supervision and in industry-related topics. They also highlight the notion that effective counsellors are not necessarily effective supervisors. According to Armstrong (2020), “professional supervisors are generally experienced, well-rounded professionals who have experience in leadership roles, policymaking, motivating others, administration, working at the coalface, and some form of knowledge that is parallel to any speciality areas in which their supervisees work” (p.33).

Effectiveness is directly linked with outcome. Thus, when measuring supervisor effectiveness, it would seem to be reasonable to step beyond the supervision session and the supervisee in a two-phase process and focus on the client and client wellbeing. How helpful is the supervision session for the supervisee? How helpful are the supervisee’s support and intervention strategies for the client?

Research findings across allied health professions suggest that effective supervisors negotiate with the supervisee a contract that clarifies roles and responsibilities. They also negotiate session agendas that reflect supervisee needs and adapt the style and content of sessions to the needs and learning style of the supervisee. Effective supervisors value the supervisory alliance and, from a platform grounded in legal and ethical considerations, they acknowledge the dignity of each participant and build positive relationships with supervisees. They create and sustain an atmosphere of trust, safety, belonging, resect and integrity (Armstrong, 2020; Leosch, 1995; Snowdon et al, 2020).

Within supervision sessions, effective supervisors use basic counselling skills such as listening, reflecting, mirroring, empathy, compassion and encouragement. They facilitate the process of supervision so that supervisees are enabled to define their own goals, to reach their own decisions and to become self-directed. They judge without being judgemental and offer clear guidance and direction when needed. They also encourage professional development and suggest resources for the supervisee to consider.

Effective supervisors are available for consultation between sessions (within reason). They support their supervisees through personal issues that may impact best practice and they promote reflective practice by providing a safe space for reflection to transform practice and promote professional growth. They demonstrate practice skills and expertise by relating practice to theory and disclosing professional knowledge that is relevant to the supervisee’s presenting concerns. They ask open questions, give frank and honest feedback and, where applicable, discuss business practices and business management strategies. They discuss industry-focused ethics and legislation and support innovative practice by encouraging supervisees to bring new ideas into their practice and service delivery.

Context of supervision sessions

Professional supervision offers the opportunity for a practising clinician and a professional supervisor to critically reflect on the supervisee’s practice, focusing on interactions across the their client base, within their workplace and across the broader industry arena. As previously stated, supervision has an educative, relational and developmental function. It is a space for mentorship and support. Supervision sessions can be individual, face-to-face supervision with supervisor and supervisee, group supervision led by a registered supervisor, or peer supervision within a collegial context of mutual support. It can also be distance mode using phone, FaceTime, Zoom or Skype. Mixed mode of face-to-face and electronic may also be an option when busy schedules in both private and professional aspects of life are the order of the day.

Undertaken at a prescheduled time and on an as-needed basis, there is a minimum requirement for clinicians to participate in professional supervision in order to maintain registration with a professional body or to work within government or agency arenas. For example, the Queensland Department of Health regulates one (1) hour per week of supervision for practitioners of under two (2) years’ experience in the field; one (1) hour per fortnight for practitioners with two to five (2–5) years’ field experience; and one (1) hour per month for practitioners with more than five (5) years’ field experience.

The recommendation of ACA for participation in supervision is one (1) hour professional supervision per 20 hours client contact, with the requirement for registration renewal being 10 hours’ participation in professional supervision per year. For supervisors to maintain registration with ACA College of Counselling Supervisor, there is a requirement of 10 hours’ supervision in addition to the 10 hours’ professional supervision. Each allied health professional association has its own specified requirements.

Types of supervision

Supervision can take many shapes and forms, some of which are defined as follows.

Professional supervision: Professional supervision is an interactive dialogue between at least two people, one of whom is a trained supervisor. This dialogue shapes a process of review, reflection, critique, support and education that incorporates evaluation of client and workplace relationships, associated administrative practices, personal and professional support, education and business practices as may be appropriate and relevant.

Clinical supervision: The focus of clinical supervision is evaluation of client outcomes with a view to enhancing professional practice skills, raising levels of competence and confidence, and ensuring quality of service to clients.

Cultural supervision: Culturally relevant supervisory arrangements explicitly recognise the influence of the social and cultural contexts. They acknowledge diversity of knowledge and plurality of meanings, and they use collaborative approaches to strengthen practice from cultural perspectives.

Group supervision: Group supervision takes place between an appointed supervisor and a group of clinicians or a multidisciplinary group. Participants can benefit from the collaborative contributions of group members as well as the guidance of the supervisor.

Peer supervision: Peer supervision applies to collaborative learning within a supervisory forums that consists of a pair or a group of professional colleagues of equal standing.

Formal supervision: Supervision that occurs in scheduled sessions and provides dedicated time for reflection and analysis in a setting that is removed from day-to-day practice is defined as being ‘formal’.

Informal supervision: Reflection and learning-focused discussions that capitalise on a heightened awareness and experiential engagement with an event is termed ‘informal’. It occurs in preparation for, during or immediately following a practice situation such as might be associated with emergency support following a critical incident. A typical example could be a cyclone, flood, drought and bushfire.

Line supervision: The focus of line supervision is on day-to-day operational matters and the supervisor is the line manager – that is, the person to whom the practitioner is accountable or the person to whom the practitioner reports within the organisational structure of the employing body.

Good supervision is not about control. It is about empowerment – empowerment of the supervisee, which leads to empowerment of the client. It will help practitioners to reflect on their own therapeutic practice, to provide the absolute best professional service to clients, and manage the complex situations and conflicting work pressures that arise.

Internal supervision: Internal supervision takes place between a practitioner and a supervisor within a work place.

External supervision: External supervision takes place between a practitioner and a supervisor who is not an employee of the same organisation/agency as the supervisee.

Supervision models

Models of professional supervision can be aligned under three umbrellas, reflecting the three differential functions: educational, relational and developmental.

There are psychotherapybased models where theoretical orientation informs the observation and selection of clinical data and where focus is on the meaning and relevance of the selected data.

Approaches underpinning psychotherapy-based models include:

■ psychodynamic, which draws on clinical data;

■ feminist, which affirms that the personal is also political and is oriented towards gender fairness, flexibility, interaction and life-span integration;

■ cognitive-behavioural approach, which focuses on cognition and behaviour; and

■ person-centred, which is grounded in Rogerian theory and focused through a perspective of collaboration (Frawley-O’Dea & Sarnat, 2000; Haynes et al., 2003; Lambers, 2007; Liese & Beck, 1997).

Developmental models are defined by stage progression as the supervisee moves from beginning practitioner to highly skilled and highly experienced practitioner. Ronnestad and Skovholt (2003) proffer the notion of a six-phase approach – suggesting that the use of ‘phase’ dispels connotation of hierarchy and sequential ordering and focuses the gradual and continuous nature of learning and development. Falender and Shafranske (2004) reference a three-levelled stepped approach where the supervisee is guided through learning experiences focused on the development of skills, abilities and knowledge, and where summative assessment of performance is ongoing and progressive. The focus on ‘competency’ is further discussed by Falender (2014) when she highlights how competency-based supervision enhances accountability.

Models of supervision that are focused through discrimination (Bernard, 1979), systems (Holloway, 1995), reflective learning (Ward & House, 1998) and schema (Haynes et al., 2003) are referred to as integrative models (Haynes et al., 2003). According to Stoltenberg and McNeill (2010), integrative models focus on counsellor development as movement over time, experience and training. It is movement that Forster (2011) refers to as a “parallel process” being born out of the ability of the supervisee to bring to supervision aspects of the client they do not know that they know, with the supervisor being drawn into reciprocating behaviour as a coexplorer of what is happening for both supervisee and the client. Forster also states, “‘Integrative’ is not a licence for a ‘personal potpourri’.” Rather, it is grounded in a deeply held and constantly reviewed sense of what is in the best interests of each client.

One of the most commonly used frameworks of supervision integration is proctor’s model. Derived from the work of Bridgid Proctor (Proctor, 2010), the model describes three aspects of the tasks and responsibilities of supervisor and supervisee: normative (management), formative (learning) and restorative (support). The ‘normative’ aspect is about maintaining standards of practice and care, the ‘formative’ highlights the educational function, and the ‘restorative’ focuses on provision of a supportive setting with space for clinicians to vent their feelings in a listening environment.

Broadly speaking, supervision models fall into three categories of operation and participation – individual, group and peer – each of which has its own benefits and challenges, as well as being empirically defined by supervisees and supervisors in the field. Characteristics of individual models include:

■ agenda that is tailored to individual needs of supervisee;

■ allowing for actual case studies to be discussed and examined without concerns of breach in confidentiality;

■ enabling supervisee to explore practice weaknesses without feeling defensive or exposed;

■ ad hoc sessions, as they are useful for providing more immediate support and learning from difficult situations that arise;

■ a trusting and supportive supervisory relationship, which can develop quickly;

■ allowing for more in-depth reflection and discussion in relation to both personal and professional matters;

■ no sense of inferiority in the presence of other practitioners who may be more experienced or more vocal;

■ supervisor and supervisee are appropriately matched;

■ resource and time-intensive; and

■ experienced and trained supervisors providing reliable ad hoc as well as scheduled sessions.

Characteristics of group models include:

■ opportunities to learn from others and appreciate alternative points of view;

■ encouragement, support and validation of experiences;

■ an efficient use of time and resources – for example, in a workplace situation, issues that are relevant to most staff, such as policies and procedures, can be discussed in group rather than one-to-one;

■ may help develop skills that are transferable to other practice situations – for example, working in teams and facilitating groups;

■ fear of being judged;

■ risk of quieter or less experienced practitioners being overshadowed or intimidated by the louder, more experienced or pushy participants;

■ interactions between members have potential to detract from learning – for example, disagreement and competition;

■ a cohesive group may make it difficult for individual or newer members to express different views or challenge the group norms, which can limit new ideas, constructive debate and sound decision-making;

■ difficulty meeting individual needs of all participants as discussions remain generalised and do not meet participants’ specific needs in a satisfactory way;

■ as issues of confidentiality need to be carefully monitored, there is little opportunity for individual participants to discuss real, current and presenting issues that arise in clinical practice;

■ clear expectations need to be set;

■ clear ground rules need to be established;

■ time needs to be carefully monitored; and

■ facilitating supervisor needs to have sound knowledge of core supervisory skills, experience and understanding of group dynamics, and the ability to adapt knowledge, skills, experience and understanding to a group supervisory context.

Characteristics of peer models include:

■ participants tend to feel less threatened and more comfortable in using skills and resources of trusted colleagues to support reflection on practice;

■ peers will usually be familiar with the situation being discussed;

■ as a sole method, this is less appropriate for the less experienced practitioner;

■ there is risk of sessions becoming chat and complain forums;

■ sessions may become too informal, lacking the process and challenge to enable growth;

■ limited opportunity for accountability and education when peers are inexperienced;

■ in the absence of a group leader, there is greater need for a clear structure and specific outcome objectives;

■ there is opportunity to be highly productive when participants are experienced; and

■ they require greater commitment from the group.

Content of super vision The nature of supervision will change over time, depending on the growth in experience and qualifications of the supervisee. For example, as discussed by Knight (2017), inexperienced supervisees would be expected to initially require the supervisor to assume more of a teaching role, helping them improve their practice and meet agency mandates. Turner-Daly and Jack (2017) suggest that as practitioners become more experienced, one might find that there is less need for case management and more need for in-depth reflection and professional development.

When using Armstrong’s RISE UP model of professional supervision (2020/2018/2003), focused discussion will incorporate aspects of:

■ evaluation (anything to do with people – such as clients, colleagues, workplace relationships, interactions within the supervisee’s practice);

■ education (modalities, interventions, professional documents, theory);

■ administration (anything to do with paper – such as ethics documents, scope of practice documents, policies, procedures, recording/reporting documentation); and

■ personal and professional support (holistic wellbeing). For supervisees in private practice, aspects of business building and business management will also be discussed. This holistic model of professional supervision is in contrast to pure clinical supervision, where the focus is on reflection, critique and review of the evaluation component as it relates to clinical work. As referenced by Queensland Health (2009), “Clinical supervision can be seen as a process that promotes personal and professional development within a supportive relationship, formed in order to promote high clinical standards and develop expertise by supporting staff and helping them to prevent problems in busy practice settings” (p8).

Good supervision Echoing the words of Morrell (2013), the essence of making the most of supervision is encapsulated within the intrinsic belief that I deserve good supervision. Good supervision is not the same as performance appraisal, crisis management, line management, complaining, counselling, debriefing, coaching, debating or chatting. However, sometimes it will contain elements of each of these.

Good supervision is not about control. It is about empowerment – empowerment of the supervisee, which leads to empowerment of the client. It will help practitioners to reflect on their own therapeutic practice, to provide the absolute best professional service to clients, and to manage the complex situations and conflicting work pressures that arise.

Good supervision will also help practitioners to recognise ethical dilemmas and clarify professional boundaries, to focus on possibility, and to challenge the self to recognise their strengths and vulnerabilities, and to find what Pearson (1991) describes as “the hero within”. From this space, the practitioner will grow in competence and confidence, develop professionally, and constantly improve the quality of practice and delivery of service.

Good supervision will also help the supervisee to feel energised, motivated and in control; to be mindful of paying attention to their holistic wellbeing – psychological, emotional, physical, spiritual; and to clarify hopes, dreams and expectations. The ultimate gift to the professional self is ensuring that one’s own supervision is good supervision and that one makes the most of every supervision session: embracing the opportunity to seek and find what James (1890) describes in terms of the conscious identity of the empirical self – that place where I meets me and I like what I see.

References

Armstrong, P. (2020). RISE UP: Relationship based integrated supervision and education to unlock potential. Stafford, AU: Kwik Kopy. (Prior versions published 2018, 2003).

Australian Counselling Association (2022). The code of ethics and practice of the association for counsellors in Australia. (Version 16). Brisbane, AU: Australian Counselling Association. (Original version published 2000).

Bernard, J. (1979). Supervisor Training: A Discrimination Model. Counselor education and supervision (CES). 19(1). pp 2-79. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.1979. tb00906.x

Davies, B. (2020). Freud at home: The Wednesday psychological society. Curator’s Blog. London. England. Freud Museum London. Retrieved from https://www.freud.org.uk/2020/05/14/freud-at-home-the-wednesday-psychological-society/

Davys, A. & Beddoe, L. (2010). Best practice in supervision: A guide for the helping professions. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley.

Dye, H., Borders, L. (1990). Counseling supervisors: Standards for preparation and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development. 69, 27-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.15566676.1990.tb01449.x. Retrieved from https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/L_Borders_Counseling_1990.pdf

Falender, C. (2014). Clinical supervision in a competency-based era. South African journal of psychology.44(1). pp6-17. doi: 10.1177/008124 6313516260

Falender C. & Shafranske, E. (2004). Clinical supervision: A competencybased approach. Washington. DC. American Psychological Association.

Falender, C. & Shafranske, E. (2010). Psychotherapy-based supervision models in an emerging competencybased era: A commentary. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(1), 45–50. doi:10.1037/a0018873

Forster, S. (2011). Integrative supervision. Contemporary psychotherapy. 3(2).

Frawley-O’Dea, M., Sarnat, J. (2000). The supervisory relationship: A contemporary psychodynamic approach. New York. NY. Guilford Press.

Gay, P. (1988). Freud: A life for our times. London, UK: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology: Volume I. pp291-401 [Etext Conversion Project – Nalanda Digital Library]. Henry Holt and Co. Retrieved from https://library.manipaldubai.com/DL/the_principles_of_ psychology_vol_I.pdf

Haynes, R., Corey, G., Moulton, PO. (2003). Clinical supervision in the hlping professions: A practical guide. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/ColeThomson Learning

Holloway, E. (1995). Clinical supervision: A systems approach. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications Inc. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452224770

Knight Z. (2017). A proposed model of psychodynamic psychotherapy linked to Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development.

Clinical psychology and psychotherapy. 24(5). pp.1029-1220. doi:10.1002/ccp.2066

Lambers, E. (2007). A person-centred perspective on supervision. In M. Cooper, M. O’Hara, P. F. Schmid, & G. Wyatt (Eds.), The handbook of personcentred psychotherapy and counselling (pp. 366–378). London. UK. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lane, J. & Herriot, P. (1990). Self-ratings, supervisor ratings, positions and performance. Journal of occupational psychology. 63(1). pp. 77-88. doi: 10:1111/j.2044-8325.1990. tb00511.x

Liese, B.S. and Beck, J.S. (1997) Cognitive Therapy Supervision. In: Watkins, C.E., Ed., Handbook of Psychotherapy Supervision, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester UK, 114133. John Wiley & Sons.

Loesch, L. (1995). Assessment of Counselor Performance. ERIC Digest. United States Department of Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED388886.pdf

Marais-Strydom (1999). Mentoring and Supervision Policy Paper: Best Practice for mentoring and supervision. OT AUSTRALIA 2000. p4.

McConnell, S. (2022), Integrated Somatic Trauma Therapy. Online course. EmbodyLab.

McMahon, M. & Patton, W. (2002). Supervision in the helping professions:

A practical approach. Frenchs Forest, AU: Prentice Hall.

Morrell, M. (2013). Supervision matters: The complete guide to reflective supervision for health and social services. Fullarton, AU: Margaret Morrell and Associates Ltd

Occupational Therapy Board of Australia, (2014). Supervision guidelines for occupational therapy. Retrieved from: https://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines.asp

O’Hanlon, B. (2000). Do one thing different: Ten simple ways to change your life. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Pearson, C. (1991).

Awakening the heroes within: Twelve archetypes to help us find ourselves and transform our world. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Pelling, N., Armstrong, P., & Moir-Bussy, A. [Eds]. (2017). The practice of counselling and clinical supervision. Samford Valley, AU: Australian Academic Press.

Pelling, N., Barletta, J., & Armstrong, P. [Eds]. (2009). The practice of counselling supervision. Samford Valley, AU: Australian Academic Press.

Queensland Health, (2009). Clinical supervision guidelines for mental health services. Brisbane, AU: Queensland Government.

Ronnestad, M. & Skovholt, T. (2003) The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development: 30(1), pp5-44. doi: 10.1023/A:1025173508081

Stoltenberg, C. & Delworth, U. (1987). Supervising counsellors and therapists. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass.

Snowdon, D. et al, (2020). Effective clinical supervision of allied health professionals: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research. 20(2). Retrieved from https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/

Turner-Daly, B. & Jack, G. (2014). Rhetoric vs reality in social work supervision: The experiences of a group of child care social workers in England. Child and family social work, 22(1). pp 36-46. doi:10.1111/cfs.12191

Victorian Government, (2012). Supervision and delegation framework for allied health assistants. Melbourne, AU: Victorian Government, Department of Health.

Ward, C. & House, R. (1998). Counseling Supervision: A Reflective Model. Counselor education and supervision (CES). 38(1). pp2-60 doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.1998. tb00554.x

Watkins, C. (2013). The beginnings of psychoanalytic supervision: The crucial role of Max Eitingon. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 2013(73), 254-270. doi:10.1057/ ajp.2013.15.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Australian Counselling Research Journal www.acrjournal.com.au