CASE STUDY

Using a psychoeducation model to support victims of adult sexual grooming

Disclaimer

WARNING: This article deals with sensitive topics relating to child and adult sexual abuse. Please do not continue if this will not be supportive of or conducive to your journey. Reader discretion is advised.

By Jaime Simpson

The sexual exploitation of another adult is the most common form of professional sexual misconduct amongst health professionals, counsellors and members of church clergy. Victims of adult sexual grooming are above the age of consent and often they do not realise they have been victimised or, when they do, they feel completely humiliated and remain silent. There are few services available to support this population group.

As a counsellor and researcher, my experience of researching and working with victims of adult sexual grooming lies is in the context of the evangelical Christian faith communities. This article will provide some background on the impact of adult sexual grooming, as well as a case study and suggested counselling ideas for working with clients who may present with the somatic symptoms that result from being a victim of adult sexual grooming.

Adult sexual grooming

Adult sexual grooming is a methodical process of forging a connection and building trust with an individual target, with the intentional goal to prepare that person for sexual exploitation (Jeglic & Winters, 2023), often disguised as mutual love. As per sexual grooming of children, sexual grooming of adults is commonly perpetrated by someone known to them, is intentional, exploitive and results in the adult victim feeling entrapped and shamed (Sinnamon, 2017).

The ‘#MeToo’ movement had a profound impact on discourse around sexual abuse and sexual harassment experiences for adult women in workplaces around the world. For faith communities, the ‘#ChurchToo’ movement started off the back of the #MeToo movement and highlighted the systemic nature of sexual harassment and sexual abuse in religious communities by members of the clergy (Allison, 2021). Adult (18+) victim-survivors who have shared their stories under #ChurchToo have revealed stories of sexual harassment, sexual abuse and grooming behaviours, generally by a senior member of the church leadership. Most of these stories remained untold until the #ChurchToo movement began.

Adults are the forgotten and silent victims of grooming and professional sexual misconduct. Due to being above the age of consent, under the #ChurchToo social media movement, adult victims often reveal they did not have the language to understand that what they experienced was abuse or sexual harassment. Counsellors or other professionals have been the ones to point out the disparity of power between professionals such as counsellors, clergy, doctors and educators that negates the process of meaningful consent. For adult victims of clergy abuse who have tried to report their experience to their church body, the response has traditionally protected abusers, blamed the victims and trivialised sexual abuse as sexual sin.

As counsellors, we need to be both abuse and trauma-informed so we can identify and name adult sexual grooming behaviours for our clients when they have experienced sexual harassment or abuse from those who hold positions of power. For any sexual relationship to be considered consensual, consent must be informed, mutual and meaningful. According to Peterson, this means: … to agree, to be of same mind, or to give permission. Informed means that all possible risks and consequences have been communicated and understood. Mutual means that the relationship is equal. Meaningful means that the client can say no without possibility of harmful consequences to self, treatment, or the relationship (1992, p. 14).

Clergy sexual misconduct

When a member of the clergy sexualises the relationship with an adult congregation member, this is like a counsellor violating the counselling relationship. The pastor’s credentials, training and elevated position require submission from those within the community and create a disparity in power – and this power imbalance undermines true consent (Fortune & Polling, 1994).

The sexual violation destabilises what should be a trusting relationship and results in the potential for significant harm for the adult congregation members’ spiritual, physical, emotional and sexual health.

Sexual misconduct amongst Christian leaders is not uncommon; research data from Baylor University indicated that around three per cent of women who attend a faith community regularly are the object of sexual advances from their leader. It is noted that in an average US church congregation of 400, seven adult women had experienced clergy sexual misconduct (Chaves & Garland, 2009). In Australia, we do not have this research data; however, if we extrapolate this international data and apply this to churches within Australia, sexual exploitation of adult congregation members may be a widespread and underresearched phenomenon.

CASE STUDY: GROOMED BY A PASTOR

Annie (name and details changed for confidentiality) was 16 when she joined her faith community; she had been invited through school and straightaway felt a real connection with God. Annie’s home life was turbulent, and joining the faith community felt like she had a whole new family. When Annie finished year 12, she wanted to go to Bible college and become a children’s pastor. She met with the senior pastor for advice on which college would be best to attend that would also allow her to stay committed to her local church. The pastor offered to mentor Annie instead; he told her he could provide for her the resources she would need to learn and, this way, she could also stay and volunteer in their home church and he would train her. Annie felt excited about this opportunity – it made her feel special.

Over time, the pastor used these mentoring sessions to get to know Annie further. He found out all about her family background and her hopes. He encouraged her to continue to come and see him for further training and support. So, she did. Little did Annie know that her pastor was grooming her. One day the pastor told Annie that he thought she was sent by God to support him and the church, and suggested they meet more regularly. Annie agreed; she felt thrilled that God was going to use her. After three months of meetings, the pastor told Annie he was attracted to her and kissed her. This resulted in a sexual act in the church office, which ended up occurring on a few occasions. She initially saw her pastor as a godly man and a father figure, so these sexual advances left Annie feeling confused, shamed and alone.

Figure 1: Lived experience of adult sexual grooming.

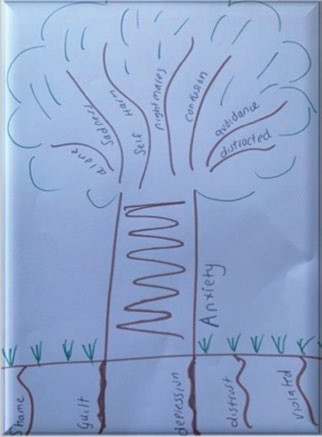

Figure 2: The impacts of grooming.

Annie told no one – she didn’t think anyone would believe her. She spent her life blaming herself, thinking she caused her pastor to sin. She dropped out of the faith community, struggled with suicidal ideation and never fulfilled her desire to become a children’s pastor. As a result of the sexual encounter, Annie has never been able to marry – she believed that her sexual purity was damaged, and no man would want to marry her.

Annie presented to the outside world as a confident lady who had chosen to remain single and focus on her career in childcare. However, she was referred to both a psychologist and counselling services by her GP because she was experiencing suicidal ideation, with the results of the Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) revealing moderate depression and severe anxiety and stress levels.

Through counselling support and going back through Annie’s childhood and relationship history, the counsellor had an opportunity to introduce to Annie the models of sexual grooming. The counsellor pointed out to Annie that she had not “tempted her pastor into sin” nor “had an affair with her pastor”, but that she had been groomed and abused by her pastor, who had the fiduciary duty to uphold his professional codes of conduct. Having an external professional educate her on the models of grooming helped Annie start to process and heal from the harms associated with her pastor abusing his position of power to sexually exploit her.

The impact

Annie had experienced significant spiritual, psychological, emotional, financial, sexual and relational harms from her experience of being groomed. The core responses of trauma were evident, including detachment, avoidance, hypervigilance, anxiety and stress that has developed into post-traumatic stress disorder. Annie felt trapped, isolated and confused. She had remained silent due to feeling like she was to blame and was concerned about the stigma of having an ‘affair’ with the minister. The spiritual and relational harm for Annie was the most damaging – her identity from age 16 was found in her spiritual relationship with God and her faith community felt like family. She felt she was now ‘impure’ after the church’s teachings on the importance of your sexual purity, and she left the community she had found a sense of family in; her foundational core beliefs and her identity were shattered.

Using models of grooming to support adult victims of grooming

As counsellors, we are to hold safe space for our clients. Victims of abuse need to regain their personal power that has been stripped away from them. This can be done by providing a non-judgemental environment that allows the client to feel safe to share their experience, confusion and questions.

A useful model to use with victims of adult sexual grooming is the Seven Stage Model of Adult Sexual Grooming by Grant Sinnamon (2017). Working through each stage of the model can support the client to understand the predatory behaviour that was employed to target them and coerce intimacy and the ultimate entrapment that occurs. Together with this model, a narrative approach can be used to personalise the client’s lived experience and identify the perpetrator’s pattern of behaviours, which helps externalise the blame and place it back to the person who caused the harm.

The client is encouraged to draw out the key elements of their own lived experienced (see figure 1). In this instance, Annie had a significant attachment to her church community and belief in God. She wanted to become a children’s pastor; in her drawing, the praying hands represent her prayers and the sun the strength in her faith. When her pastor encouraged her to rely on his teachings and serve in their church rather than go to Bible college, it made Annie feel special and loved; however, that soon turned to dark clouds around her heart. After the sexual acts, Annie felt trapped in chains and didn’t know how to escape. The fire represents her inner turmoil.

Another vital step in supporting clients who have experienced adult sexual grooming is to help them understand the impacts on their spiritual, psychological, emotional, financial, sexual and relational health (see Figure 2).

To the external world, Annie presented well, like a beautiful, strong tree. Yet, when looking at the roots of her life we see shame, guilt, avoidance, depression. These roots, once roots of spiritual connection and faith, had turned into Annie living with extreme anxiety (the trunk). The ‘fruit’ of this is displayed in the flowering of the tree; the branches reveal inner turmoil (self-harming thoughts, missing work, distraction, recurring nightmares, confusion and being unsettled). The visual representation gave an opportunity to reframe Annie’s anxiety to the core nervous system responses of trauma.

By using the ‘window of tolerance’ concept by Dan Siegal (I like to call this the ‘window of resilience’), Annie was able to identify when her nervous system would result in being dysregulated and could identify her current coping strategies, both healthy and not so healthy. Annie set goals that would include developing new emotional regulation strategies to help her heal from her trauma response and keep her within her window of resilience.

Annie was afraid to initiate any intimate relationships, fearful that she had ‘lost’ her sexual purity, but she also desired to be in relationship. By educating Annie on her rights and empowering her to establish boundaries, recognise her strengths, know her value as a human being and learn new communication techniques, the counsellor helped her develop a strong warning system that reduced the likelihood of revictimisation and strengthened her confidence in seeking new relationships.

When an adult client has been groomed, they often lose their identity and feel worthless, afraid and alone. Using a psychoeducational approach to support victim-survivors can help them gain an excellent understanding of theory as they also learn to integrate that theory into their daily lives. As they do, they regain their self-confidence, recognise their value and start to live a life free from the entrapment that has often been their story for many years.

Further research on adult sexual grooming

Best practices and safer frameworks can only be developed by hearing the voices and experiences of those who have experienced professional sexual misconduct. For her research project, Jaime Simpson is conducting an anonymous survey for adults aged 18 and over who were the target of sexual harassment or inappropriately involved with, or the victim-survivors of, pastor sexual misconduct in evangelical, Pentecostal Christian faith communities in Australia.

‘Pastor’ means any member of the clergy, leadership team or elder of any gender, and ‘sexual misconduct’ includes sexual harassment, sexual intimacy (wanted or unwanted), sexual advances or coerced intimacy.

Please see here if you would like to learn more: qsurvey.qut.edu.au/jfe/form/ SV_ 3w3Edzcda37aTUq.

About the author

Jaime Simpson is a level 4 ACA counsellor and an academic consultant based in Sydney, and has recently completed the RISE UP individual and group supervisors training. Her current focus is counselling domestic violence victim-survivors and clients living with religious trauma, and providing training and support to professionals developing their careers within this industry. She is also a unit coordinator and online learning advisor for the Graduate Certificate in Domestic Violence Responses at the Queensland University of Technology.

Jaime is currently completing her Master of Philosophy via research and holds a Graduate Certificate in Domestic Violence, Master of Counselling, Bachelor Degree in Counselling and an Advanced Diploma in Counselling majoring in child development and parenting. She also has qualifications in advanced practice in male family violence interventions, sexual violence, addiction counselling, suicide prevention, religious trauma and crisis response counselling, as well as a variety of counselling interventions (DBT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (1 and 2) and levels 1 and 2 of Gottman Marriage Therapy).

After living in Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong, Jaime has a passion to continue to explore new cultures with her family, believing the best experiences she can give her children is to introduce them to new cultures and different ways of life. Jaime believes the most helpful way to mitigate the risks of developing vicarious trauma when working in the counselling industry is to move your body. For ‘fun’ and to keep herself in balance and mitigate such risk, Jaime enjoys running in trail events. Her first 100-kilometre trail event, at Mount Kosciuszko in 2023, ended up being 108.8km!

References

Allison, E.J. (2021). #ChurchToo: How Purity Culture Upholds Abuse and How to Find Healing. Broadleaf Books

Chaves, M., & Garland, D. (2009). The prevalence of clergy sexual advances towards adults in their congregations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48, 817-824 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01482.x

Fortune, M.M.,& Poling. J.N. (1994). Sexual abuse by clergy: A crisis for the church. Decatur, GA: Journal of Pastoral Care Publications

Jeglic, E. L., & Winters, G. (2023). Adult Sexual Grooming: A Case Study. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research & Practice, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2023.2177577

Peterson, M.R. (1992). At Personal Risk: Boundary violations in professionalclient relationships. Norton & Co.

Sinnamon, G. (2017). The psychology of adult sexual grooming: Sinnamon’s seven-stage model of adult sexual grooming. In G. Sinnamon & W. Petherick (Eds.), The psychology of criminal and antisocial behavior: Victim and offender perspectives. (pp. 459–487). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0- 12-809287-3.00016-X