CLIMATE CHANGE AND MENTAL HEALTH

THE ART OF MEANINGFUL ACTION: ADDRESSING THE MENTAL HEALTH TOLL OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Embracing the concept of ‘active hope’ in her work and life, Dr Chloe Watfern’s creative-based practice draws on meaningful connections to transform people’s distress and anxiety around climate change into a more positive mindset. By Melissa Marino

Chloe Watfern was pregnant with her second child as Australia’s Black Summer bushfires raged across the east coast over 2019–20.

As a resident of Sydney, there was no escaping the smoke that choked the city from New South Wales’ worst bushfire season, and she felt the impacts both physically and psychologically.

By the time her daughter was born late in February, the fires had turned to floods. Torrential rain across several days led to power outages and evacuations and, despite the distraction of a new baby, Dr Watfern recalls being “filled with despair” about climate change.

“I really struggled with my mental health during that period,” says the artist and research psychologist, who had been involved in environmental issues for many years. “I did a lot of doomscrolling; I revisited a lot of quite alarming science. And it took me a long time to reckon with that and find my own path through it.”

Dr Watfern says she “slowly but surely” realised she could take skills from her professional background and channel her negative feelings into something constructive. So, she shifted the focus of her work to look at the connections between climate change and mental health in the community.

Dr Watfern had been completing a PhD with Black Dog Institute and the University of NSW School of Art and Design, working alongside neurodivergent artists in supported studios to better understand their art practices.

Focused around social inclusion, her qualitative research involved numerous hands-on creative projects with participants, including people with autism and dementia carers, who hand-stitched works of art on cloth to express their experience.

Given it is intended to build community and social wellbeing at a group level, Dr Watfern says there is significant overlap between the work she is undertaking today as a research associate with the Black Dog Institute and the Consumer and Community Involvement and Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform of Maridulu Budyari Gumal Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE).

Through the Institute and SPHERE, and as an independent creative facilitator, Dr Watfern has maintained the community focus of her work but has segued into addressing distress associated with climate change – a real issue for a growing number of people.

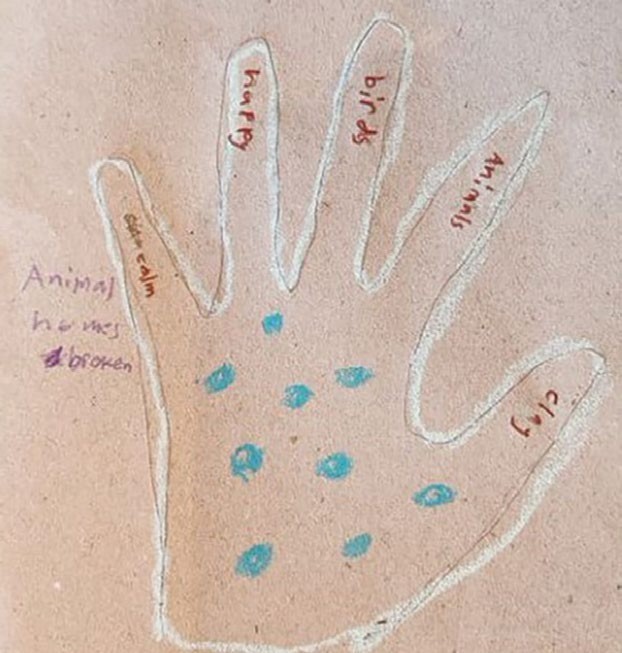

In Chloe Watfern’s body mapping workshops multigenerational participants used life-sized outlines of their bodies as scaffolds to express how they felt in nature, as well as about changes to the environment.

Photo: Chloe Watfern

Compounding people’s trauma, Dr Watfern says, is climate distress – also known as climate anxiety – that refers to concerns around future loss and uncertainty.

Climate change impacts

Dr Watfern says there is a substantial body of evidence showing that climate change is impacting on people’s mental health in several ways.

Firstly, there are impacts such as trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by those who have been impacted by climate change directly – losing homes, special places or loved ones to fires, floods and heatwaves fuelled by a warming world.

Solastalgia, a term coined by Australian academic Professor Glenn Albrecht in response to the impact of open-cut mining in the Hunter Valley, is also gaining traction globally. It describes distress or depression caused by environmental change, such as from climate change.

Compounding people’s trauma, Dr Watfern says, is climate distress – also known as climate anxiety – that refers to concerns around future loss and uncertainty.

“Many people who have lived through incredibly traumatic experiences don’t feel they can just recover and repair and it’s over,” she says. “They feel these climatefuelled events are going to keep on coming. So how do you plan for a future that’s so uncertain?”

Dr Watfern says these types of responses are not just restricted to those directly impacted by a significant natural disaster.

In a world where impacts of climate change – no matter how incremental – are seen and felt every day, the experience of climate distress is widening, she says.

“Unfortunately, the line between direct and indirect impact is becoming blurrier as the crisis escalates,” she says. “A lot of people are simply reading about these things in the news or are becoming aware of the science, or experiencing more hot days, and that is quite rightly stressful.”

A young issue

Dr Watfern says it is young people, growing up in a world already impacted by climate change and concerned about what lies ahead, who are experiencing the greatest levels of climate distress.

A 2021 global survey of 10,000 people younger than 25, led by Caroline Hickman from the University of Bath, found 80% were worried about climate change. And more than 45% said their feelings about climate change affected their day-to-day functioning.

“A lot of young people are not wanting to have children, for example, because of their anxieties about what the world will look like with climate change,” Dr Watfern says. “It’s a really big issue for them.”

Dr Watfern says much of this distress is driven by uncertainty about the future as well as a sense of hopelessness about the sheer scale of the problem. “They have questions around what they will do to cope, but also how they can contribute to a solution to such a huge issue,” she says. “So I think a lot of people feel very helpless.”

Dr Watfern is working in response to this sense of helplessness, building people’s feelings of agency and understanding through positive, arts-based activities.

Meaning and hope

As a qualitative researcher trained in psychology and art, Dr Watfern takes a ‘meaning-focused’ approach to her work, with the concept of ‘active hope’ at its core.

This framework is inspired by two eminent researchers: Dr Maria Ojala, who after more than a decade researching young people and climate change is an exponent of meaning-focused coping strategies; and Dr Joanna Macy, a scholar and environmental activist informed by Buddhism and systems change theory who co-authored a seminal text on active hope.

While unique in their own right, both of these theories hinge around acknowledging the seriousness of the issue causing distress, then drawing on someone’s personal belief system to promote, meaningful, positive action.

Working within the arts-based knowledge translation team at Black Dog Institute, Dr Watfern collaborates with communities and a range of organisations to develop creative responses to people’s experiences – including distress around climate change.

Students from Randwick Girls High School created letters of thanks to female leaders taking action on climate. Photo: Chloe Watfern

Visual artmaking, writing and dialogue enables people to explore their feelings about the climate crisis and build a constructive response, she says.

“It’s been really fruitful and a privilege to hear how people are feeling and play a role in helping them to come to terms with such a big issue,” she says.

Projects for empowerment

In one project, The Climate Letters, Dr Watfern and her collaborator Zoe Edema worked with students at Randwick Girls High School sending ‘letters of thanks’ to female leaders taking positive action on climate.

Letter writing is a powerful rhetorical tool that opens a dialogue and it enabled the students to articulate their feelings about climate change, she says.

Dr Watfern was amazed at how many of the leaders who received a letter responded. “They have said how the letter uplifted them,” she says. “So there’s ripple effects when you start heartfelt communication between people.”

Dr Watfern is also running ‘body mapping’ workshops with the Black Dog Institute and a team led by her PhD supervisor and mentor Professor Katherine Boydell, who has written a book on the role of the practice in research.

Body mapping involves taking a life-sized tracing of a person’s body to be used as a scaffold or a framework to articulate an experience, Dr Watfern explains.

In the workshops, held in collaboration with Randwick Council, she is working with children and their carers to map how they experience nature. Participants express the positive feelings they have when they are in nature and how they feel that in their body. They are also asked about how they feel about changes to the environment.

Working as families, participants create a collective map with their bodies interlinked. Dr Watfern says this opens important dialogue and cooperation between generations, helping parents to communicate with children about the issues.

Creative approaches such as letter writing and body mapping unlock different perspectives on issues causing people distress, whether it be climate or something else.

“Often it’s hard to express our concerns through usual forms of conversations, so art can help create a context where we can reveal ourselves to others,” she says. “Sometimes it’s just about the mindfulness of certain practices, like making a mark or creating an object, that helps to centre us.”

She says everyone can engage in art-based techniques to prevent distress from escalating. “It’s not just for when you’re struggling and in acute crisis,” she says. “These are habits and practices that you can use in daily life to live a richer life, and they have definitely informed my work.”

Chloe Watfern and Zoe Edema guided students in the creation of beautifully crafted letters that acknowledge and give thanks to people who are taking action on climate change. Photos: Chloe Watfern

“These are habits and practices that you can use in daily life to live a richer life, and they have definitely informed my work.”

Positive action

Dr Watfern says there are overlaps between the principles she applies in her own work and how counsellors can understand their role in helping people as they struggle with feelings about the climate crisis.

For counsellors dealing with clients presenting with these types of concerns, Dr Watfern says an important first step is not to pathologise climate anxiety. Once distress is validated, empowering responses can be explored.

“Part of not pathologising is not focusing on fixing or stopping the feelings of anxiety or distress, but looking really closely at them and what those feelings are telling us and how we can allow them to be there, without completely overwhelming us,” she says.

Using a meaning-centred approach that draws on active hope, counsellors can help people understand why they care about climate change (their love of the natural world, for example) and identify positive actions related to that, such as planting a tree, tending to a garden or even just spending time outdoors. These are lessons Dr Watfern has adopted herself, taking breaks from climate-related news, spending time in nature to remind herself why she cares, and deriving meaning from her work.

“Today I feel more fulfilled and motivated in my work than I probably was before, because I care so much about doing something,” she says. “And I still do have moments where I feel really sad and worried – particularly I have a lot of those feelings around my children and what their life will look like in 20 years’ time and what our life together will look like. But I often channel that now into things that I know I can do and contribute.”