WORKFORCE TRENDS

Illustration: 123rf

SPECIAL REPORT ON DEMAND AND SUPPLY TRENDS AFFECTING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

A special report into demand and supply trends affecting psychological industry.

ACA commissioned an independent research report to understand key demand and supply trends affecting Australia’s workforce delivering psychological services.

These are short-term treatments to improve mental health outcomes for people with common mental disorders. The Australian Government subsidises such treatments under its Better Access Initiative; however, Better Access is struggling to meet demand due to workforce shortages and other reasons. Its workforce includes GPs, occupational therapists, psychologists and social workers. Although counsellors and psychotherapists deliver these psychological services outside the Medicare system, they are not eligible to deliver them under Better Access.

Several questions motivated the research and creation of the report, Trends in Australia’s psychological services workforce: some implications for Better Access:

■ To what extent could each profession potentially contribute to reducing unmet demand in the short to medium term?

■ Could a lack of information about the workforce as a whole be impeding the ability of decision-makers to consider the full gamut of policy solutions? In this version of the report for CA, we summarise the key findings and interview report author and Brigalow Consulting founding director Alistair Davidson.

A VITAL WORKFORCE

As the founder of Brigalow Consulting, Mr Davidson specialises in helping peak bodies contribute more effectively to public policy development.

“My aim is to combine my experience in research, policy analysis and public inquiries with my interest in peak bodies.”

Mental health is a policy topic that Mr Davidson continues to find stimulating. His interest grew while working on the Productivity Commission’s landmark Mental Health Inquiry. In his view, the public policy challenge of addressing the scale and complexity of needs more effectively, efficiently and equitably remains enormous.

“Although the inquiry considerably advanced our understanding and knowledge on a broad front,” he says, “there is always more research that can and should be done.”

Using the National Mental Health Service Planning Framework, current estimates suggest a shortfall of some 7787 full-time equivalent psychologists (ACIL Allen, 2021). Understanding more about the full psychological services workforce available helps with better planning and considerations for the policy solutions to ensure Australians have timely access to quality psychological services. This is especially important in rural and remote areas of Australia, where there is more unmet demand.

DEFINING PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES

Motivating this report was the problem of unmet demand for psychological treatment under Better Access. For this reason, the report uses the term ‘psychological services’ to mean Better Access services that deliver psychological treatment. These are short-term services aimed at improving mental health outcomes for people with common mental disorders (such as anxiety and depression) and other mental health problems (such as anger and loneliness) (Productivity Commission, 2020).

Accordingly, our use of the term excludes Better Access services that are not explicitly therapeutic. These relate chiefly to preparing or reviewing mental health treatment plans. However, an exception is the inclusion of services provided by clinical psychologists that may also include psychological assessment. Although some researchers view assessments as inherently therapeutic (Hanson & Poston, 2011), data limitations precluded distinguishing treatment and assessment services in such instances. Most psychological services delivered under Better Access are focused psychological strategies (FPS). The following FPS are approved for delivery under Better Access:

■ psychoeducation, including motivational interviewing;

■ cognitive-behavioural therapy, including behavioural interventions (behaviour modification, exposure techniques, activity scheduling) and cognitive interventions (cognitive therapy);

■ relaxation strategies (progressive muscle relaxation, controlled breathing);

■ skills training (problem-solving skills and training, anger management, social skills training, communication training, stress management, parent management training);

■ interpersonal therapy (especially for depression);

■ narrative therapy (for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples); and

■ eye-movement desensitisation reprocessing (DOHAC, 2022a).

Various mental health professionals provide FPS through Better Access under three categories of service offerings:

■ ‘focused psychological strategies’ are provided by GPs, other medical practitioners and allied health providers, namely registered and clinical psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers;

■ ‘psychological therapies’ are provided by clinical psychologists; and

■ ‘mental health treatment consultations’ are provided by GPs and other medical practitioners.

While the category ‘focused psychological strategies’ includes the services listed above, in the case of clinical psychologists and GPs the category may cover a broader range of mental health service offerings beyond the delivery of treatment services alone. This includes mental health planning and psychological assessments.

DEFINING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES WORKFORCE

Given the definition of psychological services – that is, the types of treatment services available under Better Access – there are a number of ways the psychological services workforce could be defined.

Defined narrowly, it could comprise existing Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) providers who deliver services under Better Access as independent practitioners. This includes a range of professions, predominately GPs and allied health providers (clinical psychologists, registered psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers).

Defined broadly, it could expand beyond Better Access to potentially encompass a wider range of mental health professionals – both employed and working independently in private practice – including counsellors, psychotherapists, registered mental health nurses, mental health support workers, peer support workers and psychiatrists. For example, some counsellors and psychotherapists in private practice deliver psychological services on behalf of private insurers and government insurance agencies (Bupa, 2019; Medibank, 2022; SIRA, 2022).

For the purposes of this research, the psychological services workforce is defined as allied mental health professionals who are eligible to deliver psychological services approved under Better Access plus non-MBS providers who are comparably qualified and placed professionally to deliver such services, were that opportunity to arise.

For non-MBS providers, being comparably qualified means having at least a bachelor, bachelor honours or master degree in a discipline relevant to the delivery of such services. Comparably placed means working as an independent practitioner in the allied health sector. According to this definition, the main professions were taken to be:

■ counsellors;

■ GPs (working in the allied health sector);

■ occupational therapists;

■ psychologists (clinical and registered);

■ psychotherapists; and

■ social workers.

Not all providers who identify with these professions necessarily provide psychological services. For example, of the more than 11,000 social workers throughout Australia who are represented by the Australian Association of Social Workers, about a fifth are accredited Mental Health Social Workers (AASW, 2020).

Many medical practitioners who prepare mental health treatment plans choose to refer their patients to allied health providers rather than delivering the psychological services themselves. Nevertheless, in considering policy options to address unmet demand for psychological services, the potential range of service providers is broader than those currently operating under Better Access.

DEMAND FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES AND PROVIDERS

Demand for psychological services is growing with the prevalence of psychological distress. Although distress peaked in late 2021 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (Biddle et al., 2022), the prevalence of psychological distress warranting mental health support has trended up since the early 2000s (Enticott et al., 2022).

Increased demand puts more pressure on Better Access. “Use of treatment services per head of population grew at nearly five per cent a year over the past decade,” Mr Davidson says. “Presumably growth would have been higher but for access and affordability constraints.”

Job prospects for counsellors, psychologists and psychotherapists in mental health are set to remain strong. The National Skills Commission (2022) is projecting employment growth over the five years to 2026 at 14.2 per cent for counsellors and 13.3 per cent for psychologists. These rates are in the top quartile for all occupations.

1. Demand is strong for services

■ The prevalence of psychological distress that warrants support was historically high just before COVID-19 arrived in Australia in January 2020 and have been at a similar level in late 2022.

■ Demand for providers of psychological services is set to remain strong in the short to medium term.

■ Per capita use of psychological services under Better Access had been trending up before COVID-19 arrived at an average rate of 4.7 per cent a year over the 10 years to 2021–22. It is not clear what factors might have since changed to reverse this trend.

• Although use of psychological services has declined from the peak in 2020–21, it does not appear to have fallen below levels prevailing immediately before COVID-19 arrived. At that time, per capita service use was historically high and there was significant unmet demand.

• Job advertisement rates for counsellors and psychologists continue to exceed those prior to the arrival of COVID-19.

• Five-year employment growth projections by the National Skills Commission place counsellors and psychologists in the top quartile for all occupations.

2. Rural and remote areas feel shortage

In rural and remote areas, commentators continue to point to a shortage of service providers. Calls to address the workforce shortage by increasing the supply of university graduates may have little impact on unmet demand in the short to medium term. The lead times to educate and fully train allied health professionals to meet standards commensurate with MBS eligibility criteria are long, ranging from five years for counsellors and psychotherapists to eight years for clinical psychologists. Further, the likelihood that increased numbers of university graduates would immediately find employment delivering psychological services as independent allied health practitioners appears low.

PROFILE OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES WORKFORCE

In 2021–22, most (94 per cent) psychological services under Better Access were provided by psychologists and GPs. In 2021, psychologists, counsellors and psychotherapists comprised the bulk (96 per cent) of the broader psychological services workforce.

This workforce was defined as degree-qualified mental health professionals working as independent practitioners in the allied health sector.

The proportion of this workforce outside greater capital city statistical areas (25 per cent) was less than the proportion of the Australian population residing in these areas (33 per cent).

“Use of treatment services per head of population grew at nearly five per cent a year over the past decade.”

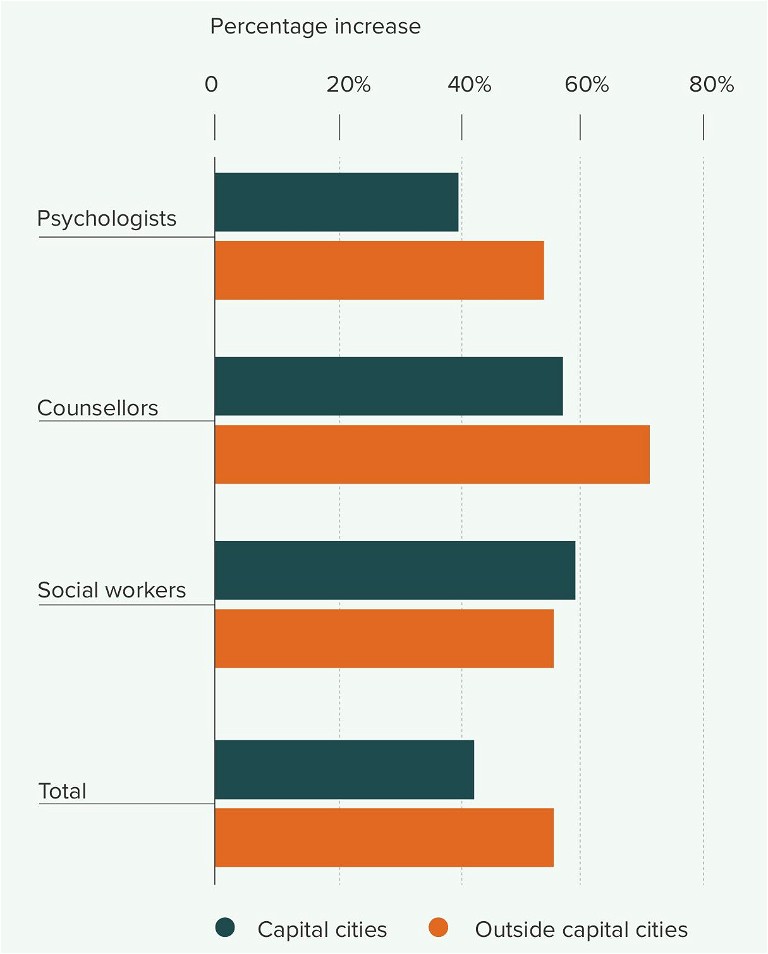

FIGURE 1 Growth in the population-adjusted number of psychologists, counsellors and social workers with a bachelor, master or doctoral degree working in the allied health sector by place of work, 2016 to 2021

Notes: Psychologist means Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) unit group 2723; counsellor means unit group 2721; and social worker means unit group 2725. Psychologists includes psychotherapists while counsellors does not as TableBuilder Basic could not identify psychotherapists within 2016 census data. The allied health sector means Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial classification (ANZSIC) industry class 8539 ‘Other Allied Health Services’. Bachelor, master and doctoral degree means Australian Standard classification of Education narrow level of education codes 31. 12 and 11 respectively. The ABS has made small random adjustments to avoid the release of confidential data.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Occupation (OCCP) by Non-School Qualification (QALLP) by Industry of Employment (INDP) by Greater Capital City Statistical Areas Place of Work (GCCSA POW), greater Capital City Statistical areas Usual Residence (GCCSA UR) [Census TableBuilder Basic, 2016 and 2021 Census of Population and Housing – Employment, Income and Education], accessed 9 January 2023.

The growth in the number of psychological service workers per head of population outside greater capital city statistical areas was highest among counsellors (71 per cent), followed by psychologists and social workers (both 54 per cent) between 2016 and 2021 (Figure 1).

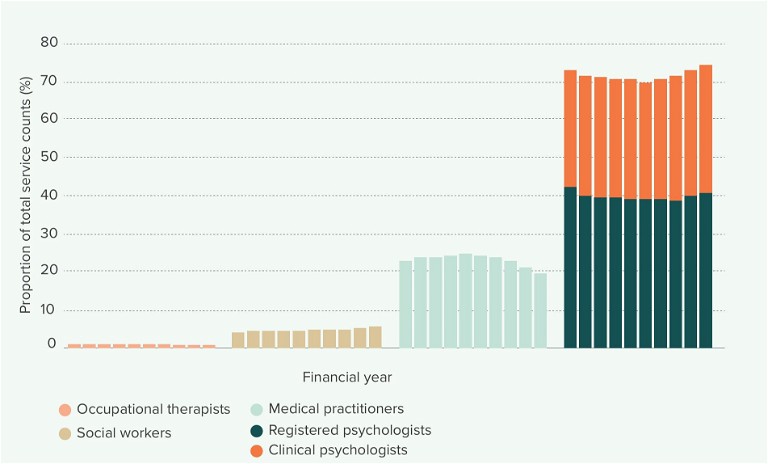

Better Access workforce

In 2021–22, psychologists provided the majority (74.3 per cent) of psychological services under Better Access, followed by medical practitioners (19.4 per cent) and social workers (5.6 per cent). The reliance on psychologists has notably increased in recent years. Since 2017–18, a significant share of total treatment sessions has shifted from medical practitioners (down 5.0 per cent) and occupational therapists (down 0.3 per cent) to psychologists (up 4.3 per cent) and social workers (up 1.0 per cent) (Figure 2).

Broader psychological services workforce

This report defines the broader psychological services workforce as degree-qualified providers of psychological services working as independent practitioners in the allied health sector. They could be providing these services under Better Access or as private providers outside of Medicare. The main professions are counsellors (including psychotherapists), GPs (working in the allied health sector), occupational therapists, psychologists (clinical and registered) and social workers.

FIGURE 2 Share of psychological services delivered under Better Access by type of service provider, 2012–13 to 2021–22

Notes: The Better Access MBS item numbers deemed ‘in scope’ for this analysis are listed in Table 1. Medical practitioners includes GPs and other medical practitioners. Source: Services Australia, Medicare Statistics: Medicare item Reports, medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp

Most of these service providers were likely to have been providing psychological services insofar as they met multiple selection criteria closely aligned with those services (there being no ABS data field specific to the provision of psychological services). While a single criterion may offer some confidence in some instances, that likelihood increases with the number of independent selection criteria. All of these providers met criteria relating to industry, occupation and qualification.

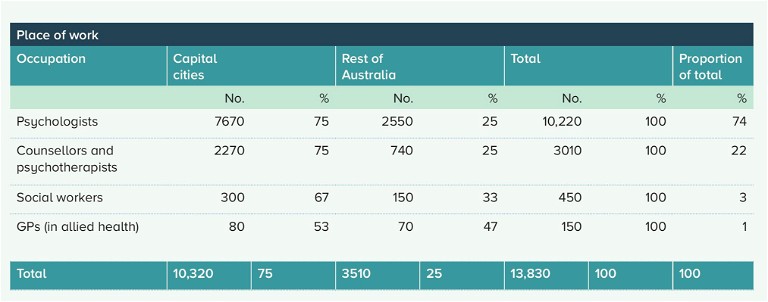

About 13,830 psychologists, counsellors (including psychotherapists), social workers and GPs who hold a bachelor, master or doctoral degree worked in allied health in 2021. Approximately 74 per cent were psychologists, 22 per cent counsellors and psychotherapists, three per cent social workers and one per cent GPs (Table 1)

ADVERTISEMENT

Unmet demand

One issue that remains unsettled is how to reduce the unmet demand for psychological therapies and focused psychological strategies (‘psychological services’). The recent evaluation of Better Access found access and wait times had worsened (Pirkis et al., 2022). Particularly affected were people on low incomes. Others have raised similar concerns (Australian Psychological Society, 2022; Productivity Commission, 2020).

A key factor is the shortage of psychologists in the mental health system. Current estimates suggest a shortfall of about 7800 (ACIL Allen, 2021).

“This is problematic because Better Access relies heavily on psychologists,” says Mr Davidson. “They provide over 74 per cent of treatment services and GPs, also in short supply, provide a further 19 per cent.”

GRADUATE ENTRY INTO THE PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES WORKFORCE

In the short term, increasing access to bachelor or master degree places to alleviate the current shortage of allied health workers delivering psychological services may have little impact on unmet need.

The lead times to educate and fully train allied health professionals to meet standards commensurate with MBS eligibility criteria are long, ranging from five years for counsellors and psychotherapists to eight years for clinical psychologists.

TABLE 1 Number of degree-qualified psychologists, counsellors, social workers and GPs working as independent practitioners in allied health by place of work, 2021

Notes: Psychologist means Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) unit group 2723; counsellor means unit group 2721; and social worker means unit group 2725. Psychologists includes psychotherapists while counsellors does not as TableBuilder Basic could not identify psychotherapists within 2016 census data. The allied health sector means Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial classification (ANZSIC) industry class 8539 ‘Other Allied Health Services’. The ABS has made small random adjustments to avoid the release of confidential data.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Occupation (OCCP) by Non-School Qualification (QALLP) by Industry of Employment (INDP) by Greater Capital City Statistical Areas Place of Work (GCCSA POW), [Census TableBuilder Basic, 2016 and 2021 Census of Population and Housing – Employment, Income and Education], accessed 9 January 2023.

The likelihood that increased numbers of university graduates would immediately find employment delivering psychological services as independent allied health practitioners appears low. In the long term, increasing access to degree programs would be expected to expand the psychological services workforce to the extent that allied health professionals who have gained experience elsewhere subsequently move into independent practice.

Meeting the shortfall

How might the Australian Government source additional psychological services workers to significantly reduce unmet need now?

“The extent to which various options have an immediate impact varies,” Mr Davidson says. “Increasing access to bachelor’s degrees is more a medium to long-term solution. The lead time to educate and fully train graduates to meet MBS eligibility criteria takes at least six years. And increasing access to master’s degrees delays workforce entry for some.

“Another consideration is the likelihood graduates would choose to deliver Better Access services,” he points out.

Graduate Outcomes Survey data between 2016 and 2021 suggests 95 per cent of recent graduates from relevant degree programs who were available for employment were not intending to begin their careers as independent practitioners in the allied health sector.

“The scope to significantly reduce unmet demand by varying policy settings for existing MBS professions appears greater in the medium to long term,” Mr Davidson says.

Allied health education and training requirements

The amount of course content in bachelor degrees that is broadly relevant to the delivery of psychological services varies considerably across fields of education, ranging from minimal (medicine) to maximal (counselling, psychology, psychotherapy).

The lead times to fully educate and train allied health professionals are long, ranging from five years (counsellors, psychotherapists) to six years (occupational therapists, registered psychologists, social workers), through to eight years (clinical psychologists).

“The biggest surprise from our research was the extent to which degree-qualified counsellors and psychotherapists were likely to be more qualified to deliver Better Access services than some other eligible health professionals.”

■ Counsellor: It takes a minimum of five years to educate and train a counsellor or psychotherapist to a level that satisfies the eligibility criteria applying to other allied health professionals who deliver FPS under Better Access.

■ GPs: It takes six-plus years to educate and train a GP to the registrar level. Bachelor degree programs in medicine typically take five to six years, but may contain relatively little practical training in mental health therapeutic interventions. To be eligible to deliver FPS health services under Better Access, GPs need to complete Level 1 and Level 2 training under the mental health training standards for GPs (GPMHSC, 2022). Depending on the training pathway, this takes about 26 hours plus the time necessary to complete pre and post-training components. A person is able to complete Level 1 and Level 2 training once they become a registrar.

■ Occupational therapist: It takes a minimum of six years to educate and train an occupational therapist to become eligible to deliver FPS health services under Better Access.

■ Psychologist: It takes a minimum of six years to educate and train a psychologist to become eligible to deliver FPS health services under Better Access.

■ Social worker: It takes a minimum of six years to educate and train a social worker to become eligible to deliver FPS health services under Better Access.

Scope to increase supply of university graduates

This report suggests that new policy proposals, which aim to significantly increase the number of university graduates available to work as independent allied health practitioners delivering focused psychological therapies, are best considered a medium to longterm solution to current shortages in the psychological services workforce. The results indicate that new policy proposals designed to increase access to bachelor or master degree places are likely to have little impact on the volume of psychological services delivered in the short term, all other things being equal.

However, in the long term, increasing access to degree programs would be expected to swell the psychological services workforce as practitioners who have gained experience elsewhere choose to move into private practice as independent allied health practitioners.

Accordingly, new policy proposals to address the shortage of independent allied health practitioners delivering psychological services would likely need to factor in:

■ the relatively long lead times to fully educate and train allied health practitioners;

■ the likelihood and timing of such additional graduates actually entering the allied health sector as counsellors and psychologists versus taking up other employment opportunities;

■ the extent to which increasing access to master degree programs, were this a viable option, could delay appropriately qualified bachelor degree graduates from becoming available for employment; and

■ constraints to training allied health practitioners, in particular, in-course training placements and post-qualification training placements.

ADVERTISEMENT

SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR BETTER ACCESS

Three implications are likely to bear on the short to medium-term effectiveness of Better Access.

1. Degree-qualified counsellors and psychotherapists are an underutilised part of the psychological services workforce. Given their qualifications, training and experience, they could play a more explicit role in a strategy to reduce unmet demand.

2. Extending MBS eligibility to appropriately qualified and trained counsellors and psychotherapists has the potential to significantly improve access to psychological services, especially outside capital cities. The relative scarcity of providers outside capital cities is likely to be inhibiting access to Better Access.

3. Expanding the range of mental health professionals who are eligible to deliver psychological services may improve the likelihood of people finding a health provider who better matches their care preferences in terms of establishing a good rapport and making them feel safe and comfortable. The limited choice in service offerings under Better Access may be discouraging some people from seeking support for their mental ill-health.

Counsellors underutilised

Could counsellors and psychotherapists play a more explicit role in reducing unmet demand for psychological services under Better Access?

“The biggest surprise from our research was the extent to which degree-qualified counsellors and psychotherapists were likely to be more qualified to deliver Better Access services than some other eligible health professionals,” Mr Davidson says.

“On that basis, extending Better Access eligibility to appropriately qualified, experienced and regulated counsellors and psychotherapists would seem a simple way to immediately improve access to affordable mental health care for many who are currently missing out.”

Understanding the capability of the entire workforce helps with developing better policy to ensure Australians have timely access to quality psychological services. This is especially important in rural and remote Australia, where unmet demand is more acute. ■

Want to know more? Read the full report:

Davidson, A. (2023). Trends in Australia’s psychological services workforce: some implications for Better Access. Research report prepared by Brigalow Consulting for the Australian Counselling Association. theaca.net.au/download-documents.php

KEY DEFINITIONS

Better Access

Better Access is the Australian Government’s main program for delivering subsidised psychological services for common mental disorders. It is known formally as the ‘Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners through the Medicare Benefits Scheme’ initiative; however, it involves other allied health professionals (Medicare Australia, 2007).

Psychological services

In the report, the term ‘psychological services’ means Better Access services delivering psychological treatments such as focused psychological strategies. These are short-term services aimed at improving mental health outcomes for people with common mental disorders (such as anxiety and depression) and other mental health problems (such as anger and loneliness). The term excludes services for preparing mental health treatment plans.

Defining the workforce

The research focused on independent practitioners, generally operating in private or group practices, who are likely to have the qualifications and training to deliver psychological services safely and effectively. The psychological services workforce was defined as allied mental health professionals who are eligible to deliver services under Better Access plus non-MBS providers who are comparably qualified and trained to deliver such services. Comparably qualified means having at least a bachelor or master degree in a relevant discipline.

References

AASW (Australian Association of Social Workers). (2020). Accredited Mental Health Social Workers: Qualifications, Skills and Experience, aasw.asn.au/document/item/11704 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

ACIL Allen. (2021). National Mental Health Workforce Strategy Background Paper [Draft Only]. acilallen.com.au/uploads/media/NMHWS-BackgroundPaper-040821-1628485846.pdf

Australian Psychological Society. (2022). Unpaid, underfunded and overworked: Psychologists on the brink [Media release, 24 February]. psychology.org.au/about-us/news-and-media/media-releases/2022/unpaid,-underfundedand-overworkedpsychologists-o

Biddle, N., Edwards, B., Gray, M., & Rehill, P. (2022). Wellbeing outcomes in Australia as lockdowns ease and cases increase – August 2022. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods. csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/covid-19

Bupa. (2019). Help for Mental Health Problems – Who Do You Call? bupa.com.au/healthlink/conditionsand-treatments/common-illnessandconditions/clinicalhealth-information/help-for-mental-healthproblems-who-do-youcall (accessed on 1 September 2022).

DOHAC (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care). (2021). Factsheet, Allied Health 2019 (Canberra), hwd.health.gov.au/resources/publications/factsheet-alld-2019.html (accessed on 17 October 2022).

Enticott, J., Dawadi, S., Shawyer, F., Inder, B., Fossey, E., Teede, H., Rosenberg, S., Ozols, I., & Meadows, G. (2022). Mental Health in Australia: Psychological Distress Reported in Six Consecutive Cross-Sectional National Surveys from 2001 to 2018. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, article 815904, 1–14. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815904

Hanson, W.E. & J.M. Poston. (2011). ‘Building Confidence in Psychological Assessment as a Therapeutic Intervention: An Empirically Based Reply to Lilienfeld, Garb, and Wood (2011)’. Psychological Assessment, 23(4), 1056–1062, doi:10.1037/a0025656.

Medibank. (2022). Mental Health Support, medibank.com.au/healthsupport/mentalhealth/support/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

Medicare Australia. (2007). Medicare Australia Annual Report 2006-07. servicesaustralia.gov.au/annual-reportarchive?context=1

National Skills Commission. (2022). 2021 NSC Employment Projections [Version 2 June 2022]. nationalskillscommission.gov.au/topics/employment-projections

Pirkis, J., Currier, Dianne, Harris, M., Mihalopoulos, C., Arya, V., Banfield, M., Bassilios, B., Buchanan, B., Butterworth, P., Brophy, L., Burgess, P., Chatterton, M. L., Chilver,

M., Eagar, K., Faller, J., Fossey, E., Ftanou, M., Gunn, J., Kruger, A., … Williamson, M. (2022). Evaluation of Better Access: Main Report [Main Report]. University of Melbourne. health.gov.au/resources/collections/evaluation-of-the-betteraccess-initiative-finalreport

Productivity Commission. (2020). Mental Health (Report no. 95). pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report

SIRA (NSW State Insurance Regulatory Authority) 2022, Workers Compensation, sira.nsw.gov.au/forservice-providers/A-Zof-service-providers/psychologists,-socialworkers-andcounsellors#Workers_compensation (accessed on 1 September 2022).

About the author

Alistair Davidson is a passionate public policy professional. He founded Brigalow Consulting after more than two decades working in government, analysing public policy and providing research evidence and advice to support the development of a wide range of government initiatives. In collaboration with other researchers, Alistair has authored over 50 reports. He is currently completing a Master of Laws.

ADVERTISEMENT