NEWS AND EVENTS

{ BOOK REVIEW }

Book

review

Photo: Pexels

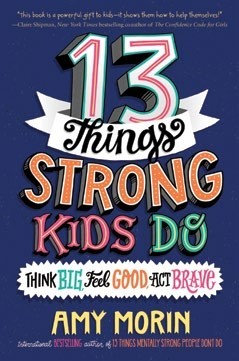

13 things strong kids do: Think big, feel good, act brave

By Amy Morin

Reviewer

Deborah Campbell

Disclaimer: I am reviewing this book through the lens of a psychotherapist and counsellor who has been working in the field, predominantly with children and young people impacted by trauma, for over 30 years. I volunteered to do this review as I’m always looking for refreshing and effective ways of working with this target group. I am a long-time reader of Counselling Australia, but a first-time contributor.

If the name Amy Morin sounds familiar, you would be right – the Scottish-born American Morin is a psychotherapist and bestselling author, as well as a podcaster and regular contributor to Psychology Today. This is Morin’s first book for eight to 12-year olds, and aims to teach them ‘how to become their best’.

The book’s hard cover features vibrant, colourful print; it is inviting from the get-go and catches your eye from the bookcase. The fonts used throughout the book are varied, perhaps to keep younger readers engaged, and readers are often addressed directly as ‘you’ (which was a little confronting to me initially). The fun illustrations are the only possible indicator of cultural diversity – and this is minimal. The chapters follow a consistent format:

• ‘the context’: This is a vignette relevant to a child-related theme, written with child friendly language and terminology – for example, ‘BFF’.

• ‘check yourself ’: A reflection/self-analysis exercise encouraging the reader to think about how the vignette may relate to some of their current thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

• ‘closer look’: This aims to help the reader draw closer parallels between the vignette and their own experience.

• ‘proof positive’: Provides examples of how the new ‘habit’ of thinking big, feeling good and acting brave can improve wellbeing.

There are three exercises per chapter (42 exercises in total) that explore:

• helpful versus unhelpful thoughts: These are about being with uncomfortable emotions and strategies to deal with them. Some exercises teach problem solving while others show readers ways to solve how they feel about the problem – because not all problems can be solved.

• traps to avoid: These are suggestions to thwart misunderstandings and avoid falling into unhelpful thoughts, and so on.

• quick tips: These are the take-aways at the conclusion of each chapter, and share how to engage the new habit (according to Morin and the researchers she has referenced at the end of the book).

The concepts are couched in cognitive behaviour theory (CBT) language, and the book is possibly the first introduction young readers will have to concepts such as positive versus negative self-talk; links between thoughts, emotions and behaviours; self-compassion; empathy; and gratitude. In addition to its array of engaging fonts, its sub-headings make it easy to read, and it also has humour and relatable characters. Trying new things is called doing ‘experiments’, which can invoke young readers’ curiosity and sense of fun and adventure.

Further positives about the book are:

• the relevant themes of the vignettes, such as belonging, social media, performance anxiety, fear of failure, risk taking, friendships and adapting to change;

• the use of metaphor; for example, “Change the channel in your brain”;

• the way it normalises making mistakes, and owning and learning from them;

• the use of quite detailed examples, so readers get a good understanding of the processes explained; for example, the STEPS problemsolving framework; and

• the way it celebrates and encourages children’s agency, empowering them to make choices where they can.

The book also has some negatives:

• It is possibly written from a ‘conservative’ American lens.

• The audiobook is narrated by an American female with a strong accent, which may impact the listening experience.

• I would have liked to see or read more references to cultural and ability diversity.

• In the scenarios the children present as middle class. There are no diverse family/ parenting models, and all parents are compassionate, understanding and wellresourced to deal with challenges (except for the character of a step-father, whose step-child calls him a a ‘jerk’).

• Some scenarios could be quite triggering for children, and while the introduction encourages readers to identify five adults they can speak with if they feel uncomfortable with any of the ideas presented or raised, not every child will have access to or feel comfortable accessing this support.

My feeling is that this book is a very useful tool for those who work with children who fit into mainstream systems; however, a practitioner or parent could adapt scenarios to better suit their reading or listening audience if they fall outside the mainstream.

My other suggestions for using the book include:

• beginning at the beginning of the book rather than selecting random chapters, as chapters often build upon the previous one;

• employing it as a family resource, as part of strengthening the family or family therapy, because it may help parents gain increased insight into some of their children’s challenges. I can imagine the book being particularly useful as an audio book (particularly if your family enjoys an American accent) – in fact, you could listen to it one chapter at a time on car trips;

• using it in group work, as it could provide meaningful opportunities for young people to reflect, with supportive facilitation, over scenarios that occured during their week, perhaps as part of a 13-week course in personal development and resilience.

Finally, if CBT makes you cringe, do not despair. There are plenty of practical exercises in this gem of a book that can be adapted to fit any strength-based, clientcentred framework.

“ Thinking big, feeling good and acting brave will help you develop bigger mental muscles. ”

– Amy Morin